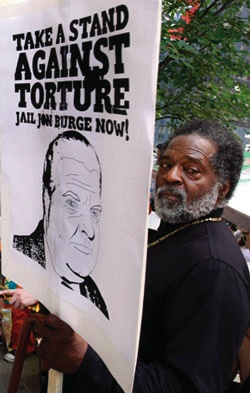

Burge panel off to slow start - Racist Chicago Cop Tortured More than 200 Suspects between 1972 and 1991

/ From [HERE] A state commission created by statute more than a year and a half ago to deal with the last of the allegations of torture against disgraced former Chicago police Cmdr. Jon Burge and [MORE] and officers under his command is still months from reviewing its first case.

From [HERE] A state commission created by statute more than a year and a half ago to deal with the last of the allegations of torture against disgraced former Chicago police Cmdr. Jon Burge and [MORE] and officers under his command is still months from reviewing its first case.

Even some members of the Illinois Torture Inquiry and Relief Commission at a recent meeting expressed frustration at the slow pace. Lawyers for some Burge accusers raise more fundamental concerns, saying they fear that while the commission is well-intended, it is destined to fall short because of its limited authority and resources.

Illinois' criminal justice system has come under intense scrutiny in recent years, culminating in the state's abolition of the death penalty last week. The ban came less than a decade after then-Gov. George Ryan emptied death row and pardoned four condemned inmates who said they confessed after being tortured by Burge or his men. Lawyers who specialize in police brutality cases estimate that as many as 20 alleged Burge victims may still languish in state prison.

A number of them have already exhausted their appeals, making the commission their last chance at justice, according to its executive director, David C. Thomas, who said he understands doubts over the commission's progress and effectiveness.

"I'd be skeptical … as well because it has been so long," said Thomas, a veteran lawyer and former professor at Chicago-Kent College of Law. "When these guys first raised their claims, nobody believed them at all. Nobody even paid any attention to them, so I do not blame them for being skeptical, not one bit."

The commission is charged with investigating claims filed by anyone — not just those accusing Burge — alleging torture by police. Its top priority, though, will be directed initially toward Burge accusers, especially those still in prison.

Burge, now 63, was fired from the Chicago Police Department in 1993 after years of allegations that he and his "midnight crew" of detectives tortured suspects in the 1970s and 1980s. They have been accused of smothering suspects with bags, playing Russian roulette with one and shocking others with a cattle prod or homemade electrical device, among other allegations.

Following a four-year investigation, a Cook County special prosecutor concluded in 2006 that Burge and his officers coerced dozens of convictions through torture. But in a controversy, the prosecutors charged no one, saying the time limit on bringing indictments had long passed.

Two years later, the U.S. attorney's office came up with a clever way to charge Burge, who was retired in Florida, indicting him on perjury and obstruction of justice charges for allegedly lying when he denied the torture allegations in 2003 as part of a civil lawsuit. A federal jury convicted him in June on all counts, and a judge sentenced him in January to 41/2 years in prison. He is scheduled to surrender to prison on Wednesday.

The commission was created by legislation passed in August 2009, but its eight voting members (there are also alternates) weren't appointed by Gov. Pat Quinn until nearly a year later. The members, who are unpaid, first met in September. Thomas officially started last month.

The commission, which has subpoena powers, will independently investigate claims, Thomas said, as well as rely on the results of previous probes such as the special prosecutor's inquiry that uncovered as many as 165 alleged coercions.

But the commission's resources are limited. In addition to the $80,000-a-year Thomas, the commission will hire only two other full-time employees — a staff attorney who will focus on investigations and a paralegal.

If a majority of the commission's eight voting members conclude there is sufficient evidence of torture, the commission will submit a written recommendation to Cook County Circuit Court's chief judge. The chief judge can then assign the case to a trial judge "for consideration," according to the statute that created the commission.

The commission has no authority to force the courts to even review a case, a critical flaw to those skeptical of the commission's effectiveness.

"What the chief judge is supposed to do with that is completely unclear," said Locke Bowman, director of the Roderick MacArthur Justice Center at the Northwestern University School of Law who has represented several Burge accusers. "The chief judge could say, 'Well, thank you very much,' and we never see the next (step)."

Pressure from the public will be key in forcing the courts to act on the commission's referrals, perhaps by granting a new trial, throwing out charges entirely or freeing an inmate from prison, said attorney Standish E. Willis, the primary writer of the law establishing the commission.

"The chief judge cannot ignore this bill and cannot ignore the recommendations of this commission," Willis said. "People are watching, and when people are watching, it makes it difficult for judges or elected officials to just kind of ignore something that people are concerned about."

Despite the concern over how the courts will respond to the commission's referrals, the commission is still months away from reviewing its first case. It must first comply with the state's open meetings law by publishing its rules and procedures and allowing public comment, a process that will take at least three to four months.

Thomas said he sympathizes with the frustration voiced by some commissioners over the pace of progress but said the commission is simply following the law while trying to determine the scope of its powers.

"It doesn't make any sense to try and cut corners," he said.

Progress will continue to be slow even after the commission begins reviewing cases, which will require the commission's small staff to examine decades-old court records and conduct interviews, said Patricia Brown Holmes, the commission's chair and a former Cook County Circuit Court associate judge.

"We're not going to do what's political, and we're not going to do what's expedient," Holmes said. "We're going to do what's right."

Attorney G. Flint Taylor, who has represented several Burge accusers, said the commission was formed with "the best of intentions." But he contended justice would be better served if Burge's accusers simply won new court hearings rather than waiting for the commission to review each case one-by-one.

"If you look at this, it's been a scandal that started in 1972," Taylor said, "and now we're almost 40 years later, and we're still dealing with it."