Vijay Prashad: The absence of U.N. and O.A.S. condemnations of Washington’s attacks on Venezuela indicates the absolute mafia-type power the U.S. wields in the world

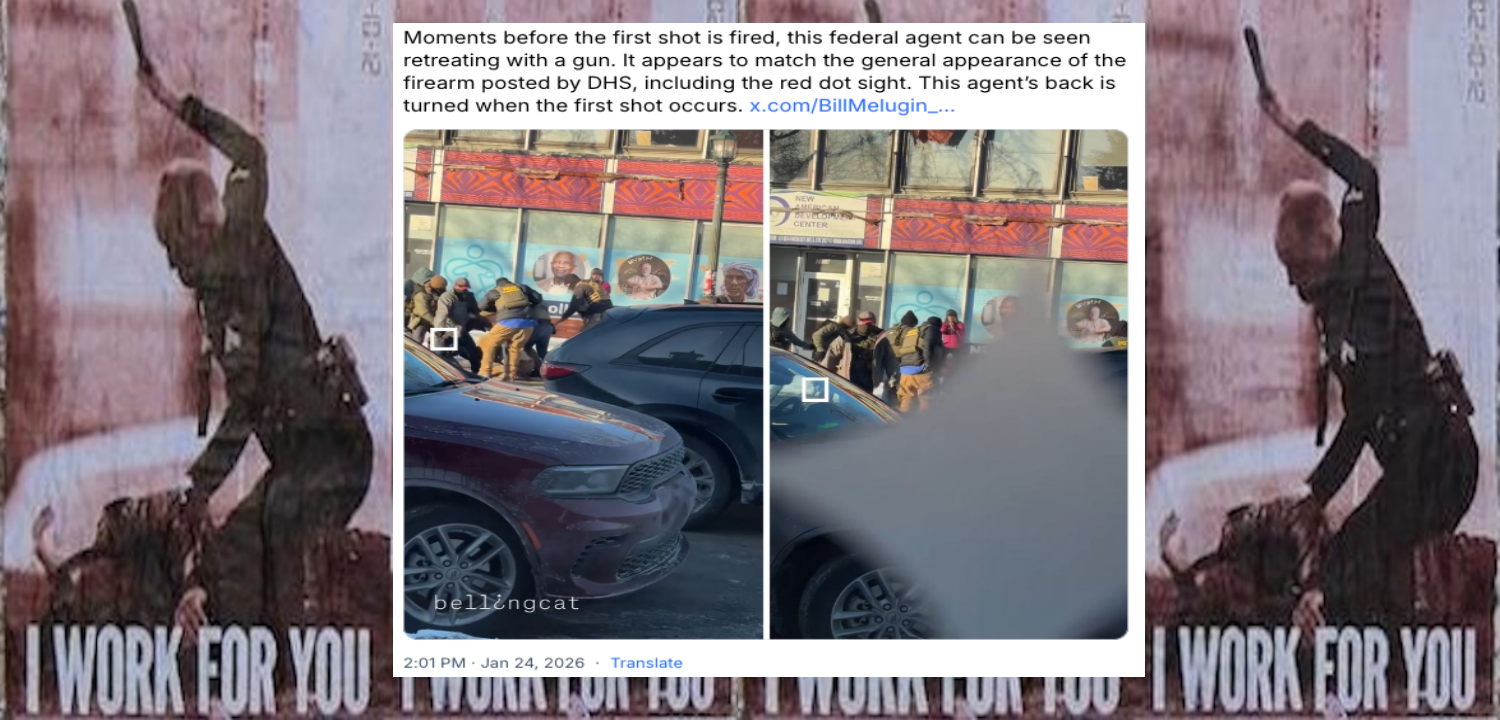

/What makes the attack against Venezuela illegal? Given the way that the United States completely and consistently disregards international law, even as it talks about a “rules-based international order,” it is worthwhile to revisit the basics of international law as well as review the international laws that the country violated with its attack on Venezuela on Jan. 3.

First, when we talk about “international law,” we are referring to legal obligations that states — and, in certain cases, international organisations and individuals — recognise as binding in their relations with one another.

From [HERE] These rules come from two main sources: treaties (written agreements) and customary international law (rules that become binding through consistent state practice and are accepted as law).

A state must consent to be bound by a treaty (which means it should either sign the treaty or accede to it), but it may be bound by customary international law and peremptory norms (jus cogens, or “compelling law,” fundamental rules that bind all states) regardless of whether it has signed any treaty.

For instance, the prohibition against genocide and slavery does not require a state to sign anything, since these prohibitions are recognised as peremptory norms that bind all states as a matter of international law.

Another way of saying this is that some laws are so fundamental that no state can opt out of them. The obligations that I will refer to below come from both sources: treaties (such as the U.N. Charter) and customary international law (including the principle of non-intervention and head-of-state immunity), sometimes interpreted and applied by the International Court of Justice (ICJ, the U.N.’s highest court for disputes between states), whose judgements carry special authority in explaining what international law requires in practice.

Prohibition of the threat or use of force. There are two key treaties that should restrict the United States’ use of force against other countries:

The most important is the 1945 Charter of the United Nations, whose Article 2(4) says that all states must refrain from the “threat or use of force” against another state. There are limited exceptions to this, such as if the U.N. Security Council, acting under Chapter VII of the U.N. Charter (Articles 39–42), determines that there is a “threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression” and then authorises the use of force to “maintain or restore international peace and security,” or if a state is acting in self-defence. Since there is no other exception, the U.S.’ act of aggression against Venezuela is in clear violation of the U.N. Charter, the highest treaty obligation in the interstate system.

In Latin America, there is also the 1948 Charter of the Organisation of American States (OAS), in which Article 21 says that the “territory of a state is inviolable” and that no “military occupation” or “measures of force” are permitted by one state against another. The OAS Charter follows the U.N. Charter, in which Article 103 makes clear that, where treaty obligations conflict, members’ obligations under the U.N. Charter prevail over those under any other international agreement.

There should already be resolutions at both the U.N. and the OAS to condemn the recent actions of the United States. The absence of such resolutions is a demonstration less of the powerlessness of the interstate system by itself and more of the absolute mafia-type power wielded by the United States in the world.

Oswaldo Vigas, Composición IV, 1943. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

Non-intervention in the internal or external affairs of a state. Article 2(7) of the U.N. Charter underscores the centrality of state sovereignty by making it clear that nothing in the Charter authorises the United Nations to intervene in matters “essentially within the domestic jurisdiction” of any state (except through enforcement measures under Chapter VII).

The prohibition of states intervening in one another’s affairs is also set out plainly in Article 19 of the OAS Charter, which says that no state “has the right to intervene, directly or indirectly, for any reason whatever” in the internal or external affairs of another state, and that includes any “form of interference” — including a military invasion and the seizure of a head of government.

The U.N. Charter and the O.A.S. Charter are treaties, and customary international law reinforces these treaty rules, independently prohibiting intervention. [MORE]