Feds Take Years to File Charges Against Cops when They Commit Crimes Against Non-White People - Holding Sovereign Cops to Different Legal & Moral Standards

/From [HERE] It was July 2014 when Eric Garner died after a violent struggle with New York City police on a Staten Island street, an encounter captured on video and replayed worldwide. When a local grand jury declined to indict any police officers, federal authorities announced in December 2014 that they would launch their own civil rights investigation.

Nearly four years later, no decision has been made on whether to file charges. “It’s a horror show,” said Jonathan C. Moore, the Garner family’s lawyer. “The family’s very frustrated.”

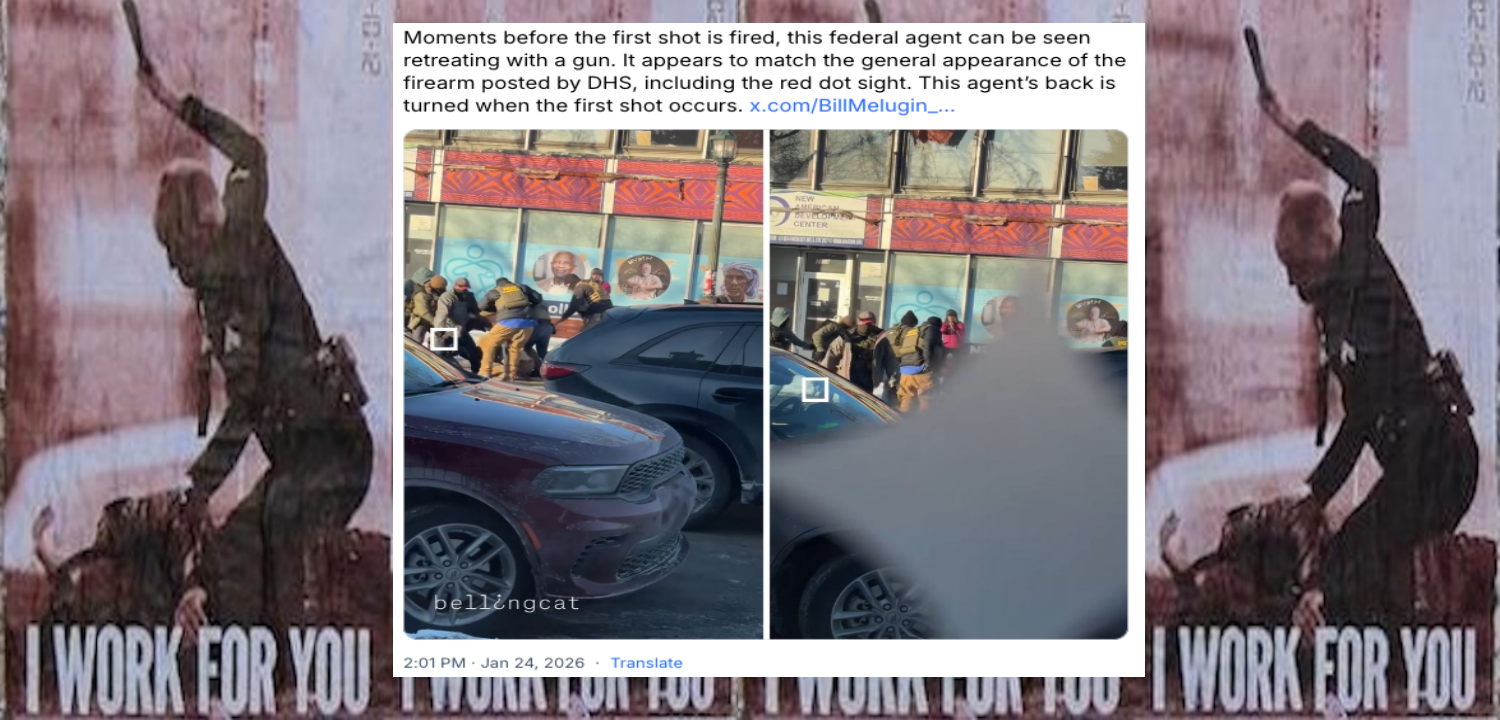

In November 2017, Bijan Ghaisar died after being shot by two U.S. Park Police officers in Fairfax County, Va., an episode also captured on video. The FBI and the Civil Rights Division of the Justice Department took over the case within three days. As the first anniversary of that killing approaches, the names of the officers and an explanation of their actions have been withheld by federal authorities. The Ghaisar family has not been told where the investigation stands.

“To wait like this is like being underwater and not being able to breathe,” said Kelly Ghaisar, Bijan Ghaisar’s mother. The family has pleaded with the Park Police and the Justice Department, held public demonstrations, and finally filed a lawsuit in search of answers to why Ghaisar, 25, was shot repeatedly in the head as he slowly steered his Jeep Grand Cherokee away from two officers. His family said he was not armed, and Fairfax County Police Chief Edwin C. Roessler Jr. confirmed this at a recent police chiefs' conference in Orlando.

The anguish of the Garner and Ghaisar families over what they see as needlessly drawn-out investigations is common for those who think they or their families have been the victim of police brutality or other misconduct.

Justice Department investigations into sworn law enforcement officers — police, jail guards and sheriff’s deputies — often take years. An examination by The Washington Post of more than 50 recent civil rights cases filed by federal prosecutors against such officers found an average of slightly more than three years elapsed from the day of the event to the day that charges were filed. The cases were all the subject of Justice Department news releases in the past year announcing either charges or a conviction in a federal prosecution of civil rights violations “under color of law.”

Those are only the cases with charges filed. A study of more than 13,000 misconduct cases submitted to the Justice Department over 20 years, conducted by the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review in 2016, found that no charges were filed in 96 percent of them.

A cumbersome process within the Justice Department for seeking charges and the high legal standard for prosecuting law enforcement officers contribute to the slow pace. In addition, law enforcement officers are sometimes reluctant to testify against colleagues, and jurors can be reluctant to convict them.

But many experts said another key factor is that no one is demanding the Justice Department move more quickly in civil rights cases to resolve the tensions of a community and the miseries of a family.

“The bottom line is there’s no pressure,” said Roy L. Austin Jr., an attorney for the Ghaisar family who was formerly a top official in the Civil Rights Division at the Justice Department. “They don’t care how long it takes because there is no one telling them they need to get it done sooner. So they aren’t concerned about the impact it may have on the community or the impact it may have on the family. That’s just their way, because they are answerable to no one except their immediate bosses.”

A number of police chiefs at the Orlando conference made a similar point, noting that leaders of federal agencies don’t have constituents who confront them at community meetings or barrage them with angry emails. Local political leaders can hold police chiefs accountable, but federal investigators do not face that pressure. [MORE]