Degenerate Republicans Praise Dr. King while Plotting to Dismantle Unions, Health Care, Education & Food Programs for the Poor

/ From [HERE] Even the Devil can quote scripture for his own purpose.

From [HERE] Even the Devil can quote scripture for his own purpose.

It is a tradition every year in mid-January that officials, determined to tear down the edifices Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. built in life, try to claim his mantle on Martin Luther King Day. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) praised King for reaching “out to people of different backgrounds, races, and creeds” and imploring “them to find the basic aspects of humanity that unite us all.” President-elect Donald Trump got an early start on King-appropriation last August, when he celebrated the 53rd anniversary of the March on Washington by calling upon “today’s leaders” to “work to ensure that all of our people can live in safety, prosperity, equality and peace.”

But these men have not honored King’s life work. They threaten the voting rights King marched to secure, as well as rights such as health care and economic security that King cherished. They praise his legacy, then actively fight to dismantle it.

“Give us the ballot,” King demanded in 1957, and African Americans will have the tool they need to protect their own interests in a democracy. Though King is remembered for his comprehensive assault on racial injustice, he viewed the franchise as the single most important component of this fight. “Our most urgent request to the president of the United States and every member of Congress,” King proclaimed, “is to give us the right to vote.”

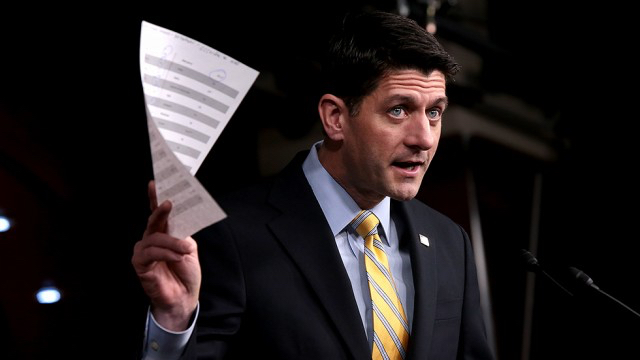

Yet Ryan refused to bring a bill restoring the Voting Rights Act to the House floor. McConnell proposed a nationwide voter suppression law. And Trump actively tried to get minority voters’ ballots tossed out.

Dr. King wept tears of joy during President Lyndon Johnson’s “We Shall Overcome” speech announcing the Voting Rights Act. He endured beatings and threats and assassination attempts to win the right to vote.

Yet Trump pledged to fill the vacant Supreme Court seat with another Justice Scalia, who voted to gut much of the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County v. Holder. And his nominee to lead the Justice Department literally prosecuted a former aide to Dr. King after that aide helped black voters cast their ballots.

In the sanitized version of King offered by men like Ryan, Dr. King was a unifying figure who paved over a racial divide that is now largely healed. But King was the arch-nemesis of Ryanism.

King saw that the battle for racial equality was inseparable from the fight for economic justice. “I am mindful that debilitating and grinding poverty afflicts my people and chains them to the lowest rung of the economic ladder,” King lamented in his speech accepting the Nobel Peace Prize. And he demanded not just civil rights but also a guaranteed income for all Americans.

And yet the Republican Party’s budget proposals, many of them authored by Speaker Ryan, may be the greatest rollback in assistance for the poor and the downtrodden since the federal government abandoned its commitment to reconstructing the South after the Civil War. It combines severe cuts to health care, education, and food assistance for the poor with major tax cuts for the rich. It is the very thing Dr. King marched against.

The curse of poverty

“Of all the forms of inequality,” King told the Medical Committee for Human Rights in 1966, “injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhuman.”

Republicans now prepare to dismantle much of America’s health care safety net. Repealing Obamacare threatens 20 million people’s health insurance. Without access to care, about 27,000 of these individuals are likely to die every year.

Speaker Ryan’s plan to privatize Medicare would increase seniors’ health care costs by about 40 percent. He hopes to cut Medicaid funding between by between one-third and one-half.

King viewed poverty as not just a tragedy, but a barbarism. “It is socially as cruel and blind as the practice of cannibalism at the dawn of civilization, when men ate each other because they had not yet learned to take food from the soil or to consume the abundant animal life around them.”

Never, since President Johnson signed the legislation creating Medicare and Medicaid, has such a comprehensive plan to foster injustice in health care been so close to becoming law.

King is remembered for his soaring moral rhetoric, but he was also unafraid to do battle with wonks. He proposed a minimum income in his 1967 book Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?, after warning that traditional antipoverty programs focusing on education, housing, or “fragile family relationships” too often operate in haphazard ways.

Housing measures have fluctuated at the whims of legislative bodies. They have been piecemeal and pygmy. Educational reforms have been even more sluggish and entangled in bureaucratic stalling and economy-dominated decisions. Family assistance stagnated in neglect and then suddenly was discovered to be the central issue on the basis of hasty and superficial studies. At no time has a total, coordinated and fully adequate program been conceived. As a consequence, fragmentary and spasmodic reforms have failed to reach down to the profoundest needs of the poor.

Having watched policymakers grope about in this way, King wrote that he was “now convinced that the simplest approach will prove to be the most effective — the solution to poverty is to abolish it directly by a now widely discussed measure: the guaranteed income.”

In offering this proposal, King shot directly at the idea that free markets will ultimately sort things out if we give them a chance. “We have come a long way in our understanding of human motivation and of the blind operation of our economic system,” the civil rights leader explained. “Now we realize that dislocations in the market operation of our economy and the prevalence of discrimination thrust people into idleness and bind them in constant or frequent unemployment against their will.”

He also argued that a guaranteed income was entirely affordable — at least in light of the other ways American chooses to spend its money. Citing the economist John Kenneth Galbrath, King estimated that his proposal would cost about $20 billion a year, “not much more than we will spend the next fiscal year to rescue freedom and democracy and religious liberty as these are defined by ‘experts’ in Vietnam.”

And, in stark contrast to men like Trump, McConnell, and Ryan, King viewed poverty as not just a tragedy, but as barbarism. “It is socially as cruel and blind as the practice of cannibalism at the dawn of civilization, when men ate each other because they had not yet learned to take food from the soil or to consume the abundant animal life around them.”

Republicans, moreover, aren’t likely to simply implement a substantive agenda hostile to King’s values. They also seek to undermine the very methods that King used to seek justice.

Dangerous unselfishness

On a winter’s day in 1968, Echol Cole and Robert Walker were crushed to death by a malfunctioning garbage truck. The death of these two Memphis sanitation workers was the latest in a long string of outrages, which also included lost overtime pay and wages so low that hundreds of these workers relied on food stamps. In mid-February of that year, 700 sanitation workers voted unanimously to strike.

Martin Luther King, Jr. died helping these men. He died helping garbage workers.

King had no illusions about the peril he faced — or the perils faced by anyone who joined him. “Let us develop a kind of dangerous unselfishness,” King preached at a Memphis church in his final sermon. It was a call to action on behalf of the striking workers, and it was a call to unite with the strikers despite the potentially terrible consequences for doing so.

King told the story of the Good Samaritan in his final sermon, but he also told the congregation what he learned during his own visit to the site of this Biblical tale.

The road to Jericho is “a winding, meandering road” which starts 1,200 feet above sea level, “and by the time you get down to Jericho, fifteen or twenty minutes later, you’re about 2,200 feet below sea level.” In Jesus’ time, King explains, “it came to be known as the ‘Bloody Pass’” because it was easy for thieves to lay in wait and ambush travelers along this road.

And so, it is likely that the men who first came upon the waylaid traveler in the Parable of the Good Samaritan had good reasons to leave without offering aid. “It’s possible,” King preached, “that the priest and the Levite looked over that man on the ground and wondered if the robbers were still around.” It was also possible “that they felt that the man on the ground was merely faking. And he was acting like he had been robbed and hurt, in order to seize them over there, lure them there for quick and easy seizure.”

Having set this scene, King then brought the church back to Memphis.

And so the first question that the priest asked — the first question that the Levite asked was, “If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?” But then the Good Samaritan came by. And he reversed the question: “If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?”

That’s the question before you tonight. Not, “If I stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to my job. Not, “If I stop to help the sanitation workers what will happen to all of the hours that I usually spend in my office every day and every week as a pastor?” The question is not, “If I stop to help this man in need, what will happen to me?” The question is, “If I do not stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to them?”

King knew that the dangers facing the men and women who joined with him were much greater than a lost opportunity to work or even a lost job. In his 1963 Letter from a Birmingham Jail, King described the preparations he and his allies would undergo before taking action. “We began a series of workshops on nonviolence,” he wrote, “and we repeatedly asked ourselves: ‘Are you able to accept blows without retaliating?’ ‘Are you able to endure the ordeal of jail?’”

King demanded solidarity at the cost of one’s own body. He did so because he knew it to be his strongest weapon against oppression. Through solidarity, “we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day,” King preached in his most well-known speech. The only way to defeat entrenched power was through collective action.

And now this, Dr. King’s greatest tool, is itself threatened by the GOP.

Unions are required by law to bargain on behalf of every employee working in a unionized shop, including workers who chose not to join the union. So if a union negotiates a pay raise — and, on average, unionized workers enjoy a wage premium of nearly 12 percent — non-members get higher pay as well.

But union bargaining is also expensive, sometimes requiring teams of lawyers and financial experts paid by the union. For this reason, union contracts frequently contain a provision requiring non-members to reimburse the union for their fair share of the cost of bargaining. That way, non-members cannot free-ride off the dues paid by members.

So-called “right-to-work” laws ban these kinds of provisions, effectively empowering workers to undermine unions by enjoying all the benefits of collective bargaining without paying their share of the costs — potentially leaving unions without the funds they need to operate. Shortly after Justice Scalia’s death, moreover, the Supreme Court split 4–4 in a lawsuit seeking to impose a right-to-work regime on all public sector unions. Once Trump appoints a replacement for Scalia, it is likely that the conservative justices will have their fifth vote.

These efforts, and similar pushes by Republican governors to undermine unions, are a direct assault on the kind of solidarity taught by Dr. King. Where King demanded that people make great sacrifices for the cause of greater justice, right-to-work laws and the like tempt workers to take what they can without thinking about what’s going to happen to their union — and eventually, the workers who depend on that union for better wages and benefits — in the long run.

There is a reason why King labeled his kind of solidarity “dangerous unselfishness.” He knew that it threatened entrenched power centers more than anything else he and his followers could engage in.

The Republican Party knows this as well, and that is why they are fighting so hard to stop it.