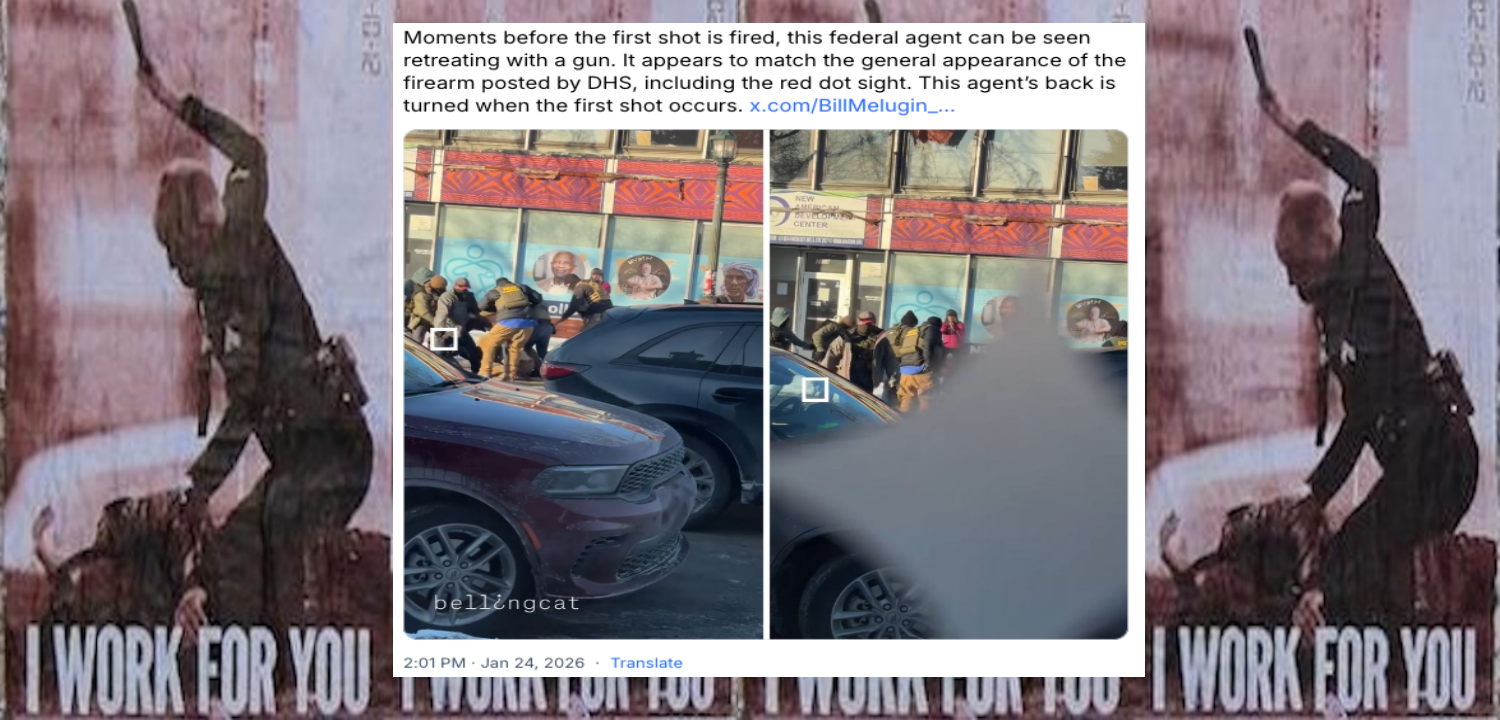

While Wearing a Cowboy Hat Neuropeon Kristi Noem Claimed a Woman “Rammed” an ICE Cop w/Her Car. In Reality the Cop Protected Himself from Danger that He Created; Moving into the Path of a Fleeing Car

/According to FUNKTIONARY

Cop Mantra – “Stop resisting arrest, stop resisting arrest, stop resisting arrest.” A pretense and precursor to murder. Everything cops say or do (including life-ending, life-wrecking abuses and/or rage-inducing bullying they routinely inflict on innocent people with impunity) needs to be looked at with extreme suspicion. Cops (patrolling predators) not only need to wear body-cameras, but they also need to be under surveillance 24/7. “If one million cobras were set loose on our city streets, wouldn’t you think it proper to know where each one was and what it was doing all the time?” ~Fred Woodworth

According to legal scholar Cynthia Lee

Officer-Created Jeopardy. Situations in which the unwise decisions or actions of the police create or increase the risk of a deadly confrontation have been called “officer-created jeopardy.” As described by one legal scholar, “[o]fficer-created jeopardy is, in essence, a manner of describing unjustified risk-taking that can result in an officer using force to protect themselves from a threat that they were, in part, responsible for creating.”

A critically important but understudied question that arises in cases involving officer-created jeopardy is whether the jury should fo- cus only on the facts and circumstances known to the officer at the moment when the officer used deadly force or whether it should be allowed to consider any facts or circumstances relevant to the reason- ableness of the officer’s use of force, including conduct of the officer that may have created or increased the risk of a deadly confrontation. In other words, is a narrow time framing approach appropriate in cases where an officer’s pre-shooting conduct may have created or in- creased the risk that the officer would need to use deadly force, or is a broad timing approach more appropriate?

Several scholars have addressed this question, primarily in the context of § 1983 litigation and how the federal courts have under- stood the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence on “excessive force” under the Fourth Amendment.76 This Article builds upon the existing schol- arship and adds an examination of this question in the context of state criminal prosecutions of law enforcement officers whose use of force has killed or seriously injured a civilian. This Article challenges the conventional wisdom that the states must follow the Supreme Court and lower federal courts when deciding what constitutes excessive police force. Contrary to popular belief, states enjoy broad authority in rafting their use of force statutes and need not follow federal civil rights jurisprudence.

Seth Stoughton, a former police officer and now a law professor at the University of South Carolina, is one of the leading voices criti- quing the narrow time framing approach embraced by a number of federal courts in the § 1983 context. In his recently published book with Jeffrey Noble and Geoffrey Alpert, Evaluating Police Uses of Force, Stoughton and his coauthors note that “[a]n officer’s use-of- force decision . . . will almost always be affected by events that occur prior to use of force itself, and often prior to the subject’s noncompli- ance, resistance, or other physical actions upon which the use of force is immediately predicated.” They also assert that the argument that an officer’s conduct prior to the use of force—what [has been] referred to as “pre-seizure conduct”—is not properly part of the analysis . . . is not only self-defeating, it also runs counter to the Supreme Court’s acknowledgment that meaningful review “requires careful attention to the facts and circumstances of each particular case.”

In A Tactical Fourth Amendment, Brandon Garrett, another leading expert on police use of force, and Seth Stoughton observe that a narrow time framing approach, under which the possibility that the officer may have contributed to the creation of the dangerous situa- tion is not part of the Fourth Amendment analysis,82 unwisely ignores the fact that sound tactical police training focuses on giving the officer time to make decisions from a position of safety.83 Garrett and Stoughton point out that a decision made early in an encounter, when there is less time pressure, can avoid putting officers into a position in which they have to make a time-pressured decision.84 Sound police tactics, such as increasing the distance between the officers and a suspect or taking cover behind a physical object that protects an officer from a particular threat, can give officers more time to analyze the situation and thus reduce the risk to officers and the subject.85 In con- trast, “[a] poor tactical decision, such as stepping in front of a moving vehicle, can deprive the officer of time in which to safely make a deci- sion about how to act, forcing the officer to make a seat-of-the-pants decision about how to respond.”86 Garrett and Stoughton argue that the training that an officer has had and the training that a reasonable officer would have received should be considered relevant circum- stances in the Fourth Amendment totality of the circumstances analysis and that constitutional reasonableness should be grounded in sound police tactics. [MORE]