Supremes Vote to Keep Genocide Cost Effective: No Liability for US Corporations Complicit in Human Rights Atrocities against Non-Whites Abroad

/From [HERE] The Supreme Court on Wednesday limited the ability of U.S. courts to hear civil lawsuits that allege corporate complicity in human rights atrocities committed abroad, but the justices did not agree on how tightly to shut the door. The justices were unanimous in stopping a case filed by about a dozen Nigerians living in the United States. They allege that a subsidiary of Royal Dutch Petroleum, the parent company of Shell Oil, aided and abetted the Nigerian government in torturing and killing people protesting the company’s operations in the Ogoni region in the 1990s.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. wrote that one of the “oldest laws on the books” — the 1789 Alien Tort Statute — did not sanction such a suit, and that “relief for violations of the law of nations occurring outside the United States is barred.”

The legislation, passed by the first Congress, has been used by human rights lawyers to sue individuals who took part in abuses abroad and corporations involved in foreign abuses, as long as the firms have some presence in the United States.

Peter Rees (a white man) Shell’s legal director, said in a statement that the decision “makes clear that the Alien Tort Statute does not provide a means for claims to be brought in the U.S. which have nothing to do with the U.S.” He added that the company denies the allegations “in the strongest possible terms.”

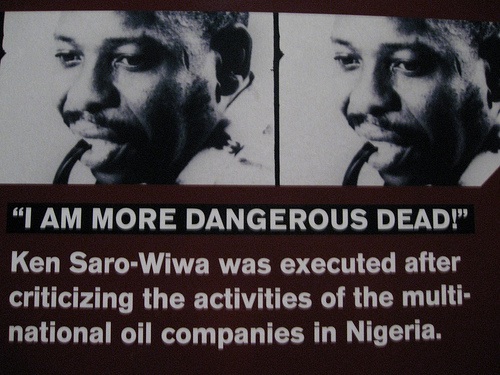

Between 1993 and 1995 MOSOP, a coalition of Nigerian environmental and human rights activists fighting against Royal Dutch Shell’s destructive oil development in their region, faced a violent crackdown carried out by the Nigerian government’s paramilitary forces. Over 800 people were killed, and 30,000 violently displaced from their homes. The founder of MOSOP – author, playwright and political activist Ken Saro-Wiwa – was a key figure in the protest movement, campaigning that the people of Ogoniland, one of the largest oil producing regions in Nigeria, should be compensated with a percentage of the oil profits, with the claim that the devastation to the land was ruining the livelihood of the indigenous people living there.

The Nigerian government sent in its forces and eventually arrested Saro-Wiwa claiming that the disruption of oil production was considered treason. Ken Saro-wiwa and 8 other activists, including another prominent Nigerian, Dr. Barinem Kiobel, were hanged by the military junta in 1995. [MORE]

Paul L. Hoffman, the attorney representing Esther Kiobel and others in the suit, said the decision was “deeply disappointing.” But he said the justices’ splintered reasoning makes it “much less clear” what the ruling means for future cases.

The law, signed by President George Washington, allows federal courts to hear “any civil action by an alien for a tort only, committed in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States.” But it was rarely invoked until the 1970s.

Roberts seemed skeptical that any case involving foreign companies and acts committed overseas would overcome the presumption against extraterritoriality in legislation Congress passed.

In the Kiobel case, Roberts wrote, “all the relevant conduct took place outside the United States. And even where the claims touch and concern the territory of the United States, they must do so with sufficient force to displace the presumption against extraterritorial application.”

He quoted an 1822 opinion by Justice Joseph Story that “no nation has ever yet pretended to be the custos morum of the whole world,” which Roberts defined from the bench as “guardian of morals.”

His opinion was joined by the rest of the court’s conservatives — Justices Antonin Scalia, Anthony M. Kennedy, Clarence Thomas and Samuel A. Alito Jr.

But Kennedy appended a short concurrence saying the opinion was narrow enough to leave open “a number of significant questions.” He said “proper implementation of the presumption against extraterritorial application may require some further elaboration and explanation.”

The court’s liberals agreed that the allegations in the Kiobel case “lack sufficient ties” to the United States. But they disagreed with the majority’s reasoning on extraterritoriality.

Justice Stephen G. Breyer said he thought the Alien Tort Statute could apply when the defendant’s conduct “substantially and adversely affects an important American national interest, and that includes a distinct interest in preventing the United States from becoming a safe harbor (free of civil as well as criminal liability) for a torturer or other common enemy of mankind.”

Breyer was joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

The court first accepted the case in late 2011 to decide whether the law applies to corporations or only to individuals. But at oral arguments in February 2012, it became clear that some justices wondered whether it should apply to any acts committed overseas, and the court ordered new arguments.

Roberts wrote that the law was spurred by incidents involving foreign nationals that occurred in the United States. One exception to presuming that law applies only to acts committed on domestic soil, he said, would be pirates.

“Applying U.S. law to pirates, however, does not typically impose the sovereign will of the United States onto conduct occurring within the territorial jurisdiction of another sovereign,” the chief justice wrote. “Pirates were fair game wherever found.”

Breyer picked up the theme in his concurring opinion. “Who are today’s pirates?” he asked. ”Certainly today’s pirates include torturers and perpetrators of genocide. And today, like the pirates of old, they are ‘fair game’ where they are found.”

In a case involving a more recent federal law, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in April 2012 that the Torture Victim Protection Act of 1991 allows lawsuits against individuals overseas responsible for torture and killing but does not permit torture victims to sue corporations or political groups such as the Palestine Liberation Organization.

The case is Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co.