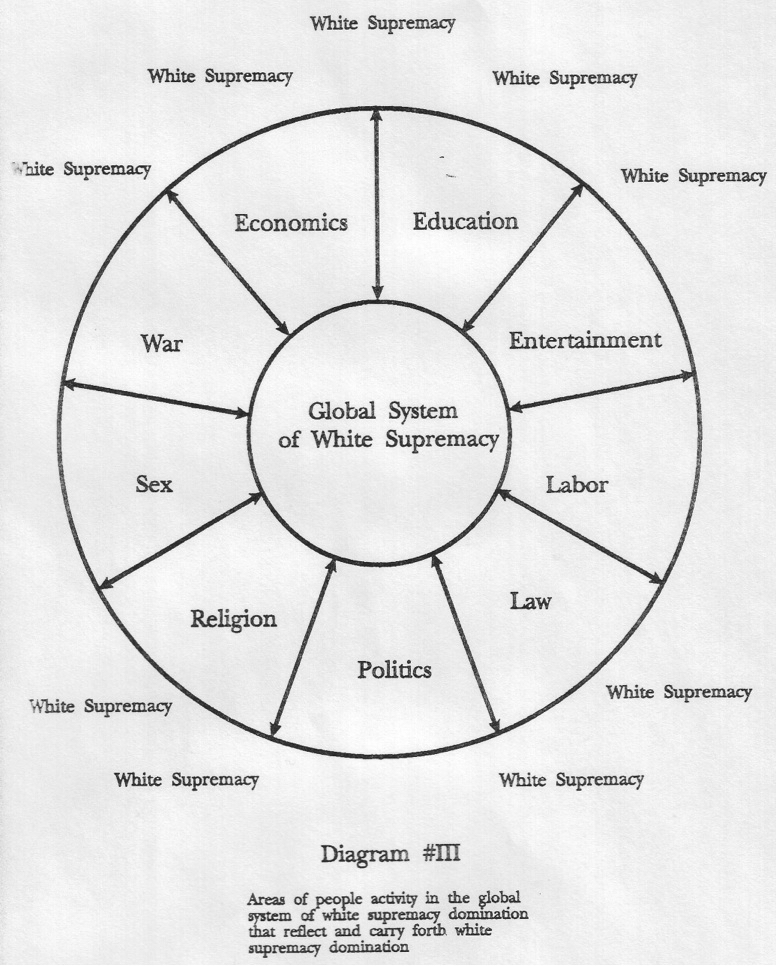

70% of Homeless in Oakland are Black. Just Another Statistical Coincidence or Symptom of White Supremacy System?

/From [SF Chronicle] Roberto Delgado gathered an armful of leather brogues and oxfords that had been placed on Northgate Avenue in Oakland by a passing motorist.

They were size 10, too small for him. But they were in good condition, and he knew someone in his community would want — no, need — a pair of shoes without holes in the soles.

Delgado didn’t leap out of the chair in front of his tent fast enough to sift through the sweaters and pants that were also dropped off. And the portable speaker, which could have been sold or traded for toiletries, cigarettes — anything — was long gone before he made it to the fresh pile of goods.

Delgado, 27, was wearing black Air Jordan sneakers, a black Raiders T-shirt and a black North Face jacket — clothes he either found or were given to him.

Black is also Delgado’s race.

It’s the race of many of the residents in the Northgate Avenue tent encampment under the Interstate 980 overpass.

And it’s the race of most of Oakland’s homeless population, which jumped by 25 percent to 2,761 between 2015 and 2017, according to a recent point-in-time count.

Dig into the city’s homeless statistics, and you should be moved by what they suggest: Black people in Oakland are more likely to lose their homes and end up homeless on the city’s streets than any other racial or ethnic group.

According to a survey administered by Alameda County weeks after the point-in-time count, almost 70 percent of the people living on Oakland’s streets are black. Yet black people were 28 percent of Oakland’s 2010 census population. And, 58 percent of Oakland’s homeless people said money issues were the primary cause of their homelessness. What’s more, 48 percent said rent assistance might have prevented their homelessness while 36 percent said employment assistance would have kept them in their homes.

That data should be dismaying to everyone, especially those who champion Oakland as a diverse, inclusive city.

“It is heartbreaking, but it is not surprising, that even in a city that has embraced black achievement ... we’re still dealing with the structural injustice in our economy,” said Councilwoman Lynette Gibson McElhaney, who represents the district that includes most of the tent cities.

She said the disproportionate number “of black people in the tents really just demonstrates that whole continuum of injustice that we see from the cradle to the grave.”

Black communities were once deprived of loans and investment, a practice known as redlining. But it’s those same communities that were targeted for subprime mortgages and loans, which left many drowning in debt and unable to make the payments necessary to keep their homes.

Then there’s folks like Marcus Emery, who got an astronomical rent increase. Emery, 53, said the rent on his Milton Street apartment jumped from $800 to $2,100, and he could no longer afford it. He moved to the Northgate camp and has been outside for nine months.

“I had a home for 18 years,” said Emery, lifting his shirt to show me the scar from a stab wound he suffered two months ago in the tent he now secures with a padlock. “It’s my first time out here. It’s so cruel.”

The convenient narrative about homeless people is that they’re lazy, mentally ill or drug addicts. Or just looking for handouts. But that’s not true. Stop by any homeless encampment, and you’ll likely find people who will tell you they simply can’t afford to keep a roof over their heads — and that they have nowhere else to go but the sidewalks under highway overpasses, where it’s cool in the summer and dry in the winter.

Oakland leaders have stressed that they’ve learned from San Francisco’s mistakes in dealing with homelessness. I wonder what Oakland has learned from San Francisco about its dwindling black population.

Delgado, an East Oakland native who told me he’s on a housing waiting list, has been homeless for four years since he was kicked out of his parents’ house. He didn’t tell me why.

“I just want to live peacefully and get a job again,” he said. “I’m just doing what I can. I don’t have nothing right now.”

Two weeks ago, he had a job doing home construction. But he lost his job.

Outside his tent, Delgado offered his neighbor, Shonee Stringer, 50, the shoes he had picked up. But they weren’t her partner’s size. He let her take a few drags from his cigarette, because that’s what most of the neighbors on Northgate Avenue do for each other: They share.

“It’s what we should be doing,” Delgado said. “If everybody did that, we wouldn’t even be in this situation.”